The Tecnique of Pericardiocentesis

Excerpt information courtesy of The Journal of Critical Illness -- July 1987, D. H. Spodick, MD, DSc

The Technique

Drainage of pericardial fluid is the definitive treatment of cardiac tamponade. Removal of even a small volume of fluid can rapidly improve blood pressure and cardiac output, and may ultimately prove to be lifesaving.

The pericardium can be tapped from almost any reasonable location on the chest wall. However, for the usual “blind” pericardiocentesis, the subxiphoid approach is preferred. Ideally, 2-D echocardiograpy is used to guide needle insertion and the subsequent path of the needle/catheter. The patient may either be recumbent or positioned so that his chest is at a 30-degree angle from the bed.

|

The needle is then inserted into the left xiphocostal angle perpendicular to the skin and 3 to 4 mm below the left costal margin. The needle is advanced directly into the inner aspect of the rib cage; the depth of perpendicular penetration depends on the amount of overlying soft tissue.

|

|

|

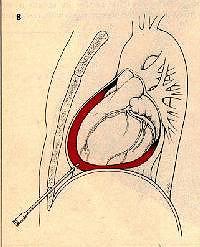

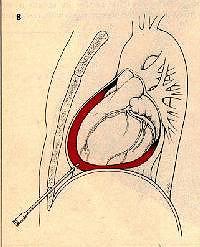

The hub of the needle is then depressed so that the needle points toward the left shoulder. Using a slow, cautious “warm gear” turning action of the fingers, the needle is advanced about 5 to 10 mm of until fluid is reached.

Zoom in on Figure B.

|

|

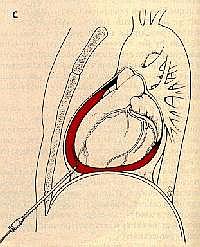

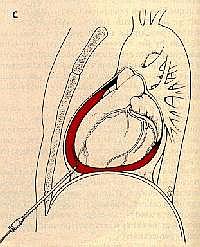

The fingers may sense a distinct "give" when the needle penetrates the parietal pericardium. Successful removal of fluid confirms the needle's position. The syringe is then disconnected from the needle and the flexible tip of the guidewire is advanced into the pericardial space under fluoroscopic guidance.

Zoom in on Figure C.

|

|

|

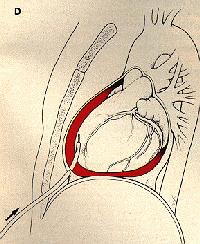

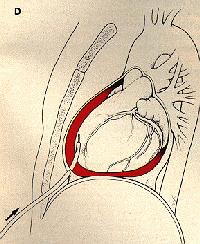

The needle is withdrawn and replaced with a soft, multihole pigtail catheter using the Seldinger technique. After dilating the needle track, the catheter is advanced over the guidewire into the pericardial space.

Zoom in on Figure D.

|

The Results

Successful aspiration of fluid (even the first, relatively small aliquot) should result in rapid improvement in blood pressure and cardiac output, with a decrease in atrial and pericardial pressures, a simultaneous decrease in the degree of any paradoxical pulse, and a decrease or disappearance of any electric alternation.

Complications

The major complications of pericardiocentesis are laceration of a coronary artery or a ventricle and perforation of the right atrium or a ventricle. Other risks include perforation of the stomach or colon, pneumothorax, arrhythmias, tamponade, and hypotension (perhaps reflexogenic).

Go to the Emergency Room by clicking the "BACK" button at the top left of your browser.

to the Emergency Room by clicking the "BACK" button at the top left of your browser.